Introduction

In December 2020, the React team released a “special Holiday Update”. This included an hour long talk by Dan Abramov and Lauren Tan as well as an accompanying demo where people could try out an exciting new technology called “React Server Components”. It’s been a long journey from that point, and the underlying API’s have changed a bit since then, but RSC’s are finally reaching a point of maturity.

History of SSR in React

So, you could— in theory— render the markup on the server, and then attach all the event handlers and instantiate all the backing views on the client. Two completely separate machines! —Jordan Walke, JSConf 2013

While it has been able to pre-render applications on the server since near its inception, React Server Components are quite different from traditional Server-Side Rendering in React. Within months of its public release, API’s like renderToString started to take shape . However, they only produce a visual representation of the current state of the application. Essentially, traditional SSR with React is based on converting the requested page’s tree of React Elements into a string of HTML.

Unfortunately, this must be fully re-constructed into a virtual DOM when it gets to the user’s browser so that things that depend on JavaScript like event listeners will work correctly. To reap the SEO and initial load benefits that SSR provides, the entire application must be rendered twice. First, when the string representation is created on the server, and then again when it is hydrated on the client with a call to the render method on the root element.

The Double Data Problem

For that render function to work correctly on the client, we also need to send over all of the code required for every single component that needs to be rendered. So, we run the JavaScript on the server to get the HTML. Then, we send it all over to the client— just to run it again and get the same, exact result. This issue is sometimes known as the “Double Data Problem”.

And, you don’t want to dump all that work every time the user clicks a link. Even if you render each page on the server, it still behooves you to provide the improved navigation experience of a Single Page Application on the client. So, you also have to load even more JavaScript for a client-side router.

The Uncanny Valley

Beyond that, there are a multitude of new things to worry about as the developer must now optimize how quickly they “hydrate” the HTML. While client-rendered SPA’s may not be fully search engine optimized, at least those developers never have to worry about problems like the “Uncanny Valley”. This term describes the hopefully brief period where things like buttons don’t work because they haven’t been hydrated yet.

Even though the user can see a full visual representation of the page, they can’t interact with it until of the JavaScript has been parsed and evaluated. This is a problem that is unique to SSR with modern frameworks, and it can lead to a very frustrating user experience. So, you don’t want to send over too much JavaScript, but you also don’t want to send over too little.

Spinner Hell

To maximize your core web vitals, you have to be extremely careful about how much JavaScript you load initially. However, you also want to be able to provide a dynamic, personalized experience for your users. Early React apps relied on Flux architectures which evolved into things like Redux for managing state and GraphQL to help with data-loading.

These rely on a global store that can be used to cache data. However, it can be difficult to split up the data requirements of each page into separate chunks. As time went on, with few first-party tools to help with data-loading, ideas like JAMStack became popular.

This is a way of building applications that rely on pre-rendered HTML to build as much of a shell of the application as possible. This is cached on a CDN so that it loads extremely quickly. Then, the rest of the data is loaded in the browser using things like useEffect and fetch. Unfortunately, this can lead to applications that are not much more than an empty shell full of loading spinners hiding client-side data-fetching waterfalls.

The Emergence of Meta-Frameworks

JAMStack was always more of a state of mind than an actual guide to building applications. Composing together the data requirements of a modern application can be extremely difficult. This is especially true when you are trying to render each page both on the server and the client. It can be hard to split up not only the data requirements of each page, but also the code required to load that data.

So, frameworks like Next.js have become extremely popular. They provide a way to statically analyze the requirements for each page and then build a single, optimized bundle for each one. They remove much of the mental overhead involved with efficiently loading data in a React application. In fact, a React core team member tweeted that “If you use React, you should be using a React framework”.

The Future of React

While a whole host of techniques have been developed by the community for rendering dynamic data as efficiently as possible, the React team have been developing a first-party solution for these problems for quite some time now. Eventually, in 2018, the React team started to iteratively release parts of this solution.

The key to it all was originally called Suspense for Data Fetching. The first tools provided for this were React.Suspense and React.lazy. However, React.Suspense cannot be used to its full data fetching potential outside of either a Server Component context or the Relay Framework. So, this limited it to just helping with code-splitting for most developers for a long time.

Although this series of articles will be primarily focused on React Server Components which are internally codenamed Flight by the React team, RSC’s are completely dependent on their earlier research into HTTP streaming codenamed Fizz. The original release of streaming SSR was with React 16.0 in September 2017. This stuff takes time!

What Are React Server Components?

In a lot of ways, server components is “Suspense for Data Fetching”. That’s what that is. We’re not calling it that anymore, but that is our first-class, like, this is the solution we think for the best way to compose data requirements into your app. —Andrew Clark, React Roundtable: Server Components, Suspense, and Actions

While there are obvious benefits to streaming by itself, the React team have gone even further. Essentially, React Server Components allow you to completely pre-render certain static portions of your UI into a serialized representation on the server. However, unlike traditional SSR, this is not a string of HTML, and none of the JavaScript necessary for building those components ever needs to be sent to the client.

The Benefits of RSC’s

The implications of this architecture are mind-blowing when fully considered. For instance, you don’t need to worry (as much) about the bundle size of the dependencies used in each server component as they will not be sent to the client. But, this is just the tip of the iceberg in terms of DX & performance benefits.

You can even use the server to do things like make calls to your database inside of your component. You no longer have to choose between figuring out how to bounce back authentication requests using things like useEffect while trying to hide critical environmental variables in the browser or hoisting everything out into a getServerSideProps call. Instead, server components allow you to enjoy the classic unidirectional flow of data that React has always championed.

You don’t even have to worry about leaking any secrets because that code will never run in the browser. This is because it is fully serialized into a special data format colloquially known as the RSC Payload. This contains encoded instructions that React uses to transform this serialized representation into valid HTML on the client.

State & Server Actions

As I said at the beginning of this section, it is a common mistake to think that server components are completely converted into HTML on the server. That’s actually how the old renderToString API from react-dom/server worked. Instead, when react-server-dom-webpack runs the function for each server component, it produces a React Element— a JSON representation of the HTML.

Most importantly, this object is then serialized so that it can be sent over the network. Because the render process only occurs once on the server and it must produce something serializable, this means that server components are stateless. So, you cannot have any side-effects because the very concept of an effect requires a stateful environment. Thus, with no useState or useEffect, server components are static by nature.

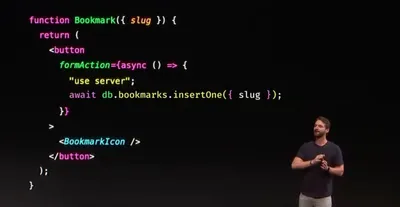

However, we are no longer limited to building purely static websites with server components as the React team have recently unveiled server actions. This is a form of Remote Procedure Call which can be used to request fresh server components. They are immensely powerful, and I think the potential DX benefits will be plain to see when we explore how they work in closer detail in chapter six.

RSC & SSR

Because they do not actually produce HTML, React Server Components are usually paired with traditional server-side rendering. This is for the same reason that SSR has always been popular— SEO, progressive enhancement, and less visible loading. Because RSC’s are rendered to a serializable format, this doesn’t even need to occur on the same server— at least until the first Suspense boundary.

In fact, the example implementations promote an architecture where the RSC’s are rendered on a separate server which can be deployed regionally on the edge. These are controlled by a global server that is responsible for SSR. While it is beneficial in many ways, it’s important to note that SSR is not strictly required for implementing RSC’s.

When you are server rendering an app built with server components, one counter-intuitive thing is that the SSR server is actually acting as a “client” in this scenario. Because the server components are not valid HTML, the SSR server still needs to process them along with all of the client components. Thus, “client components” still need to worry about things like whether or not the window object is available to avoid hydration errors.

The Current RSC Landscape

From the React perspective, when we put on our React hats (even people who work at Vercel), their goal is to prove out the paradigm, figure out how the pieces should fit, and figure out how to make React better… On the one hand, I get a lot of criticisms of Vercel. On the other hand, it just gets under my skin when people say that Vercel tells the React team what to do. When… actually, it’s more complicated. The reality is that Vercel has invested years into building out our vision. —Dan Abramov, “React Core Panel” by Joe Savona, Ricky Hanlon, Dan Abramov, & Michael Jackson at #RemixConf 2023 💿

At the time of this writing, the Next.js app router is around eleven months old. Developers have been able to use server actions in Next.js for around a third of that. One intrepid developer has even built dev tools for it. So, why haven’t any other frameworks fully adopted React Server Components yet?

Vercel, Next.js, & React

The obvious answer is that this stuff is just really complicated. It’s not the easiest thing to implement, and the API’s are rapidly changing. While several of the members of the React core team now work at Vercel, none of this code is hidden away. Everything is open-source.

Having the ability to rapidly prototype these features in a production framework like Next.js gives the React team the ability to throw things at the wall and see what sticks. It’s easy to imagine how things should work, but reality can be brutal when that imagination meets production applications with hundreds of external dependencies.

So, while some have complained about this being some sort of inside advantage given to Vercel, it doesn’t change the exigency of this partnership in guiding the development of React Server Components. And, it doesn’t necessarily pay to be an early adopter. The Next.js team has received many complaints about the performance of the development server of the app router (although this has admittedly improved recently).

Hydrogen & Remix

The Hydrogen team at Shopify were the first to adopt React Server Components. They soon abandoned them. In fact, Shopify went so far as to immediately purchase Remix as a replacement. Chief among the Hydrogen team’s complaints was the strict yet nebulous separation between the server and the client. They claimed that the way RSC’s blurred these boundaries made things too complicated for their engineers.

The React team used this experience to guide changes to some key implementation details. For instance, in the original RFC, server and client components were resolved using a special filename syntax of .server.jsx and .client.jsx respectively. Now, this has been changed to use client directives at the top of files for client components and use server directives for server actions that can be more granular.

Ironically, Ryan Florence has recently announced that a future version of Remix will be based on React Server Components although he has recently expressed doubt about how soon that will be achieved. In fact, an experimental proposal was unveiled by core team member Jacob Ebey literally the day before I published this. It seems we’re getting closer and closer to a Remix based on React Server Components.

Update: 11/21/2023

Michael Jackson and Ryan Florence have officially announced that they will be going forward with the experimental proposal. So, Remix will be adopting React Server Components in the near future.

To be fair, the Shopify team have always said they still believed in the technology. It just doesn’t always pay to be the canaries in the coal mine. This is especially true when real users are involved.

Why Am I Doing This?

A lot of people think it’s about data loading. That’s just a minor piece of it… Remix is all about levers— on letting you move code to the server and keep it out of the browser so that you have better performance… And, RSC is just another one of those levers that lets us move even more stuff over to the server that you don’t actually need. You’re making a network call for JSON anyway. Like, just get the elements! You don’t need the templates in the browser. —Ryan Florence, Syntax 649: Supper Club × Ryan Florence of Remix

Basically, I have a bad habit of wanting to know how everything I use actually works. This manifests in me taking these crazy deep dives. The only way to pull myself out of these rabbit holes is to attempt to record the accumulation of my knowledge with these articles. Writing everything down brings order to my mental chaos as I formalize the disparate threads of my thoughts into an interwoven narrative that acts as a rope with which I can escape. I will admit that I didn’t expect this rabbit hole to run so deep. Okay, enough with the metaphors.

This all started this summer. I created a series of silly demos in response to the challenges presented at the end of Dan Abramov’s incredible article, RSC From Scratch. Part 1: Server Components. I wanted to complete as many of them as possible without using react-server-dom-webpack which is the real way of using React Server Components.

I hoped this would help show the basic ideas behind how things like client components work. Eventually, I ended up using RSDW to help me with streaming due to my inexperience in that area at that time. I do have to recommend JSer’s similar article on the subject for going where I would not.

In the end, there were several different versions of the app. The ones that used react-server-dom-webpack show how to simply implement streaming server components, but we didn’t make any kind of module map which is required for client components. So, while this gave us access to Suspense for data fetching, we weren’t fully taking advantage of the new architecture.

The other final versions showed how to do a silly hack on top of the experimental Node loader and RSC server that Dan Abramov included in the demo. I used it to do a runtime transformation of each client component so that they could be registered in the browser. This allowed for a cheap version of the powerful code-splitting that RSC’s provide.

However, there were many issues with my naive implementations which would make them worthless in any kind of production environment. Most of these were due to my stubborn refusal to properly use the official libraries provided by React. So, after finishing that series, I decided to take a closer look at how one would go about creating a real RSC framework. After over four months of research & delirium, I think I’m starting to understand.

Stuff You Should Know

While we teach, we learn. —Seneca the Younger, he probably said that.

I am not an expert by any means. I hate to have to say this at the beginning of each series, but I don’t want anyone to think that I’m some kind of charlatan. I only learned JavaScript at the beginning of 2022. I fell in love with it to an extreme degree, and now I’m a bit obsessed.

While I have spent months researching this, I am certain that I will make a few inaccurate assumptions. This is the entire reason why I have a comments section. Please, don’t hesitate to correct me on even the most minor of details.

Seriously, call me out when I’m wrong. I would really appreciate it. Above all else, I want these articles to be accurate. This is a learning exercise after all.

While I plan on this series being absurdly detailed and really diving deep into how RSC’s work, I also want it to be approachable by novices like me. So, I will be spending quite some time explaining some fundamental concepts of the web platform with lots of links to sources if you want to know more.

But, I also can’t cover everything. You should probably come into these articles with a basic understanding of how JavaScript and React work. You don’t need to memorize React’s reconciliation algorithm, but basic concepts like components and state are required knowledge here.

Finally, it is extremely important to note that these APIs are not finished. The React team are making pull requests multiple times a week, and things are changing rapidly. Much of what you read today will likely change soon. My plan is to try to keep these articles as up-to-date as possible, but I can’t promise that I will be able to keep up with the React team. It’s been an interesting challenge so far.

Conclusion

What if you could take Partial Hydration but then re-render the static parts on the server? If you were to do that you’d have Server Components. You’d have a lot of the same benefits of Partial Hydration with the reduced component code size and the removal of duplicate data, but not give up maintaining client side state on navigation. —Ryan Carniato, Why Efficient Hydration in JavaScript Frameworks is so Challenging

In this series of articles, I will attempt to document my understanding of how React Server Components work by methodically expounding on each detail piece by piece. Overall, there will be fifteen chapters. They will range between 3,000-12,000 words, and each one will have an accompanying video summary. The articles will be exhaustive, so I’ll try to keep things light and entertaining in the videos.

Five of these chapters will be strictly diving through the React code. But, we’re going to need a lot of background information to understand what’s happening there. So, I’m dedicating four full chapters to explaining the way that certain Web APIs and JavaScript interfaces work. The first two major chapters will be like this, so we won’t go deep into the React code base until chapter four.

Along the way, we will explore the wide world of the web platform as we learn about some of the abstractions employed by the React team. I’m going to try my best to explain just enough of such seemingly abstruse concepts as streaming, promises, and proxies for you to see why the React team have designed the API in the way that they have. To help with this, I’ve built over a hundred interactive demos to try to show how each of these things work.

The next chapter will start us off with a journey through the history of asynchronous JavaScript. From the very first web browsers to the emergence of server components, we’ll try to understand why JS evolved into what we have today. The third chapter will focus solely on streams, and then we’ll start diving into the React codebase.

We’ll initiate ourselves with the React codebase by exploring react-server-dom-webpack. This is what Next.js uses to make RSC’s work. We will quickly see that it simply provides useful environmental wrappers around the core libraries react-server and react-client. So, we will fully unwrap each of those libraries as well as we eventually compose an intricate web of connections between them.

After exploring those three libraries, I’ll briefly talk about the other RSC implementation package react-server-dom-esm as well as the hopefully upcoming react-server-dom-vite. Then, we will dive into the ways people have actually been actually implementing these libraries. We’ll start with some extremely simple frameworks, but we will end with attempting to understand the way RSC’s work in Next.js.

Finally, we will build a simple framework ourselves. This won’t be much more complex than the examples that already exist in the flight demos in the fixtures folder of the official React repository, but we’ll put our own spin on it to try to maximize simplicity and ease of understanding. It’s all for the sake of education, but after these articles perhaps you will be able to contribute to one of the frameworks that we will cover.

If you absolutely can’t wait to learn anymore about RSC’s, this article is full of links. However, there are two recent talks that I want to specifically highlight. Mark Dalgleish did a great job breaking down his mental model with code examples at React Advanced. And, Ben Holmes showed off his work live at React Summit. Both of these are well worth your time.

I’m going to try to release one chapter a week, but I’m not going to make any promises. I’m doing this for fun, and I don’t want to burn myself out. I have over 100,000 words in my notes and a lot of video recorded, but editing is never thrilling. The writing is the fun part. I hope you enjoy reading these articles as much as I enjoyed writing them. I’ll see you next week as we start by learning about streaming in JavaScript.